An operating system has to work closely with the hardware system that acts as its foundations. The operating system needs certain services that can only be provided by the hardware. In order to fully understand the Linux operating system, you need to understand the basics of the underlying hardware. This chapter gives a brief introduction to that hardware: the modern PC.

When the ``Popular Electronics'' magazine for January 1975 was printed with an illustration of the Altair 8080 on its front cover, a revolution started. The Altair 8080, named after the destination of an early Star Trek episode, could be assembled by home electronics enthusiasts for a mere $397. With its Intel 8080 processor and 256 bytes of memory but no screen or keyboard it was puny by today's standards. Its inventor, Ed Roberts, coined the term ``personal computer'' to describe his new invention, but the term PC is now used to refer to almost any computer that you can pick up without needing help. By this definition, even some of the very powerful Alpha AXP systems are PCs.

Enthusiastic hackers saw the Altair's potential and started to write software and build hardware for it. To these early pioneers it represented freedom; the freedom from huge batch processing mainframe systems run and guarded by an elite priesthood. Overnight fortunes were made by college dropouts fascinated by this new phenomenon, a computer that you could have at home on your kitchen table. A lot of hardware appeared, all different to some degree and software hackers were happy to write software for these new machines. Paradoxically it was IBM who firmly cast the mould of the modern PC by announcing the IBM PC in 1981 and shipping it to customers early in 1982. With its Intel 8088 processor, 64K of memory (expandable to 256K), two floppy disks and an 80 character by 25 lines Colour Graphics Adapter (CGA) it was not very powerful by today's standards but it sold well. It was followed, in 1983, by the IBM PC-XT which had the luxury of a 10Mbyte hard drive. It was not long before IBM PC clones were being produced by a host of companies such as Compaq and the architecture of the PC became a de-facto standard. This de-facto standard helped a multitude of hardware companies to compete together in a growing market which, happily for consumers, kept prices low. Many of the system architectural features of these early PCs have carried over into the modern PC. For example, even the most powerful Intel Pentium Pro based system starts running in the Intel 8086's addressing mode. When Linus Torvalds started writing what was to become Linux, he picked the most plentiful and reasonably priced hardware, an Intel 80386 PC.

Looking at a PC from the outside, the most obvious components are a system box, a keyboard, a mouse and a video monitor. On the front of the system box are some buttons, a little display showing some numbers and a floppy drive. Most systems these days have a CD ROM and if you feel that you have to protect your data, then there will also be a tape drive for backups. These devices are collectively known as the peripherals.

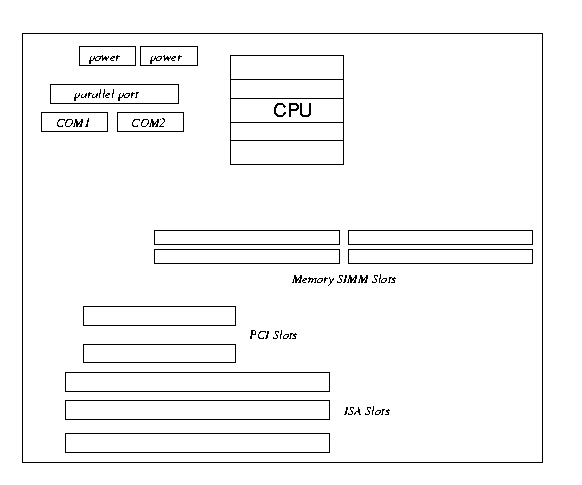

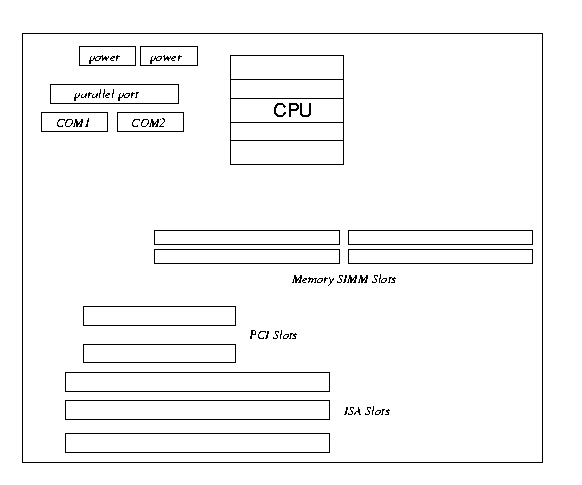

Although the CPU is in overall control of the system, it is not the only intelligent device. All of the peripheral controllers, for example the IDE controller, have some level of intelligence. Inside the PC (Figure 1.1) you will see a motherboard containing the CPU or microprocessor, the memory and a number of slots for the ISA or PCI peripheral controllers. Some of the controllers, for example the IDE disk controller may be built directly onto the system board.

The CPU, or rather microprocessor, is the heart of any computer system. The microprocessor calculates, performs logical operations and manages data flows by reading instructions from memory and then executing them. In the early days of computing the functional components of the microprocessor were separate (and physically large) units. This is when the term Central Processing Unit was coined. The modern microprocessor combines these components onto an integrated circuit etched onto a very small piece of silicon. The terms CPU, microprocessor and processor are all used interchangeably in this book.

Microprocessors operate on binary data; that is data composed of ones and zeros.

These ones and zeros correspond to electrical switches being either on or off. Just as 42 is a decimal number meaning ``4 10s and 2 units'', a binary number is a series of binary digits each one representing a power of 2. In this context, a power means the number of times that a number is multiplied by itself. 10 to the power 1 ( 101 ) is 10, 10 to the power 2 ( 102 ) is 10x10, 103 is 10x10x10 and so on. Binary 0001 is decimal 1, binary 0010 is decimal 2, binary 0011 is 3, binary 0100 is 4 and so on. So, 42 decimal is 101010 binary or (2 + 8 + 32 or 21 + 23 + 25 ). Rather than using binary to represent numbers in computer programs, another base, hexadecimal is usually used.

In this base, each digital represents a power of 16. As decimal numbers only go from 0 to 9 the numbers 10 to 15 are represented as a single digit by the letters A, B, C, D, E and F. For example, hexadecimal E is decimal 14 and hexadecimal 2A is decimal 42 (two 16s) + 10). Using the C programming language notation (as I do throughout this book) hexadecimal numbers are prefaced by ``0x''; hexadecimal 2A is written as 0x2A .

Microprocessors can perform arithmetic operations such as add, multiply and divide and logical operations such as ``is X greater than Y?''.

The processor's execution is governed by an external clock. This clock, the system clock, generates regular clock pulses to the processor and, at each clock pulse, the processor does some work. For example, a processor could execute an instruction every clock pulse. A processor's speed is described in terms of the rate of the system clock ticks. A 100Mhz processor will receive 100,000,000 clock ticks every second. It is misleading to describe the power of a CPU by its clock rate as different processors perform different amounts of work per clock tick. However, all things being equal, a faster clock speed means a more powerful processor. The instructions executed by the processor are very simple; for example ``read the contents of memory at location X into register Y''. Registers are the microprocessor's internal storage, used for storing data and performing operations on it. The operations performed may cause the processor to stop what it is doing and jump to another instruction somewhere else in memory. These tiny building blocks give the modern microprocessor almost limitless power as it can execute millions or even billions of instructions a second.

The instructions have to be fetched from memory as they are executed. Instructions may themselves reference data within memory and that data must be fetched from memory and saved there when appropriate.

The size, number and type of register within a microprocessor is entirely dependent on its type. An Intel 4086 processor has a different register set to an Alpha AXP processor; for a start, the Intel's are 32 bits wide and the Alpha AXP's are 64 bits wide. In general, though, any given processor will have a number of general purpose registers and a smaller number of dedicated registers. Most processors have the following special purpose, dedicated, registers:

Some processor's stacks grow upwards towards the top of memory whilst others grow downwards towards the bottom, or base, of memory. Some processor's support both types, for example ARM.

The cache and main memories must be kept in step (coherent). In other words, if a word of main memory is held in one or more locations in cache, then the system must make sure that the contents of cache and memory are the same. The job of cache coherency is done partially by the hardware and partially by the operating system. This is also true for a number of major system tasks where the hardware and software must cooperate closely to achieve their aims.

All controllers are different, but they usually have registers which control them. Software running on the CPU must be able to read and write those controlling registers. One register might contain status describing an error. Another might be used for control purposes; changing the mode of the controller. Each controller on a bus can be individually addressed by the CPU, this is so that the software device driver can write to its registers and thus control it. The IDE ribbon is a good example, as it gives you the ability to access each drive on the bus separately. Another good example is the PCI bus which allows each device (for example a graphics card) to be accessed independently.

There are times when controllers need to read or write large amounts of data directly to or from system memory. For example when user data is being written to the hard disk. In this case, Direct Memory Access (DMA) controllers are used to allow hardware peripherals to directly access system memory but this access is under strict control and supervision of the CPU.